Insights

Help your clients reach their goals by staying on top of the economy, markets, and investment strategies. Simply tap into timely insights and analysis from our senior leaders, economists, and investment experts.

|

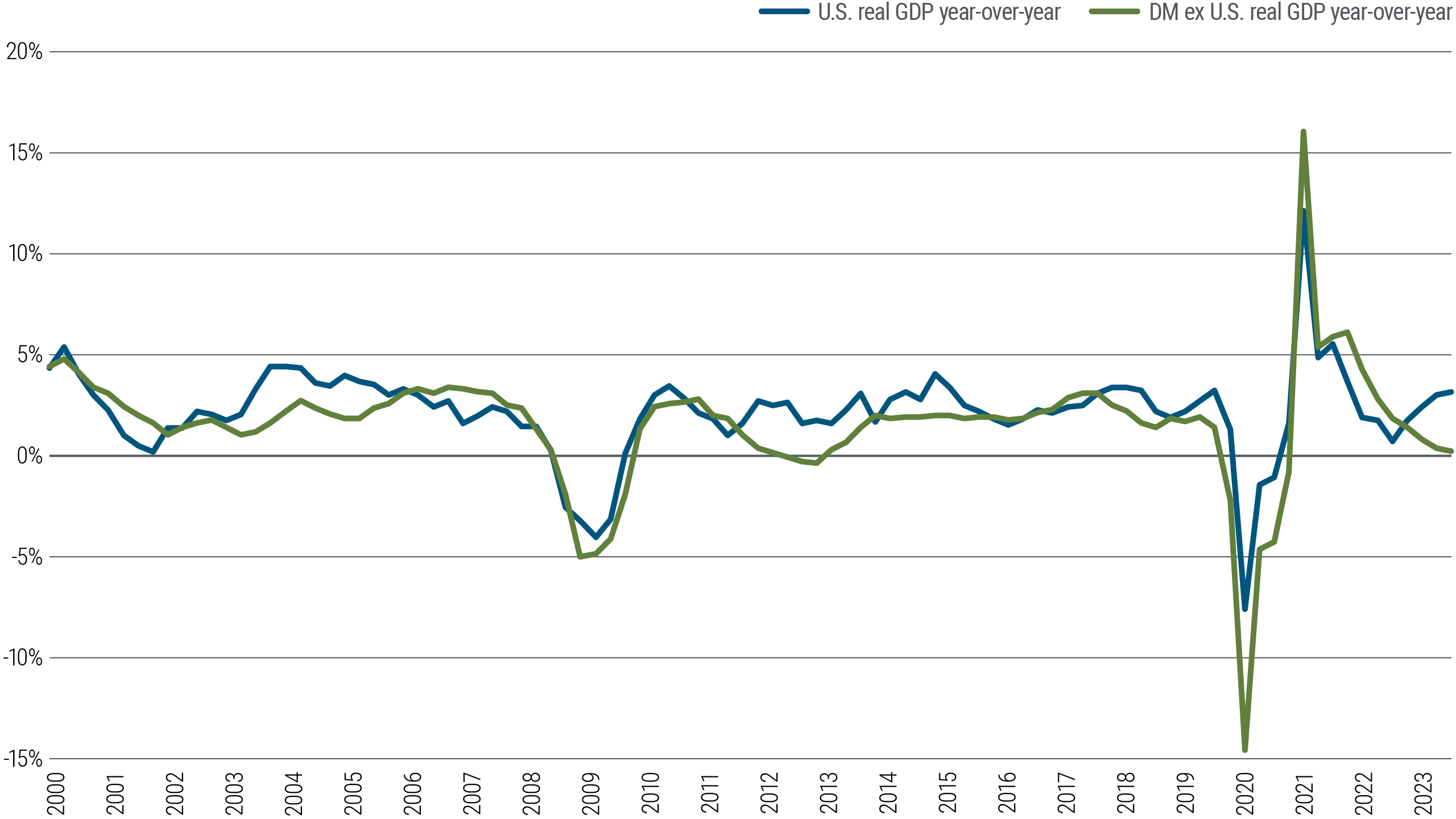

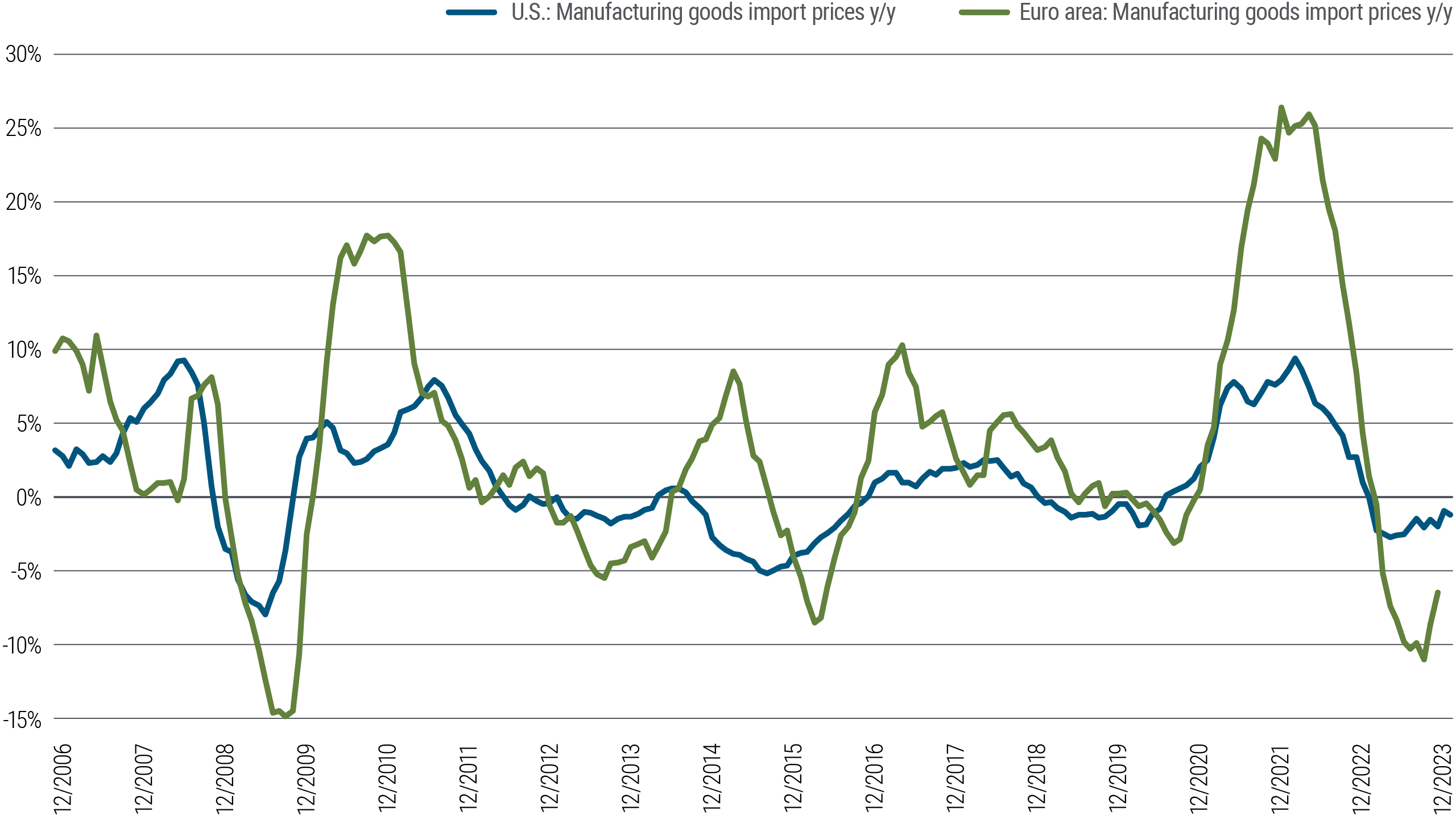

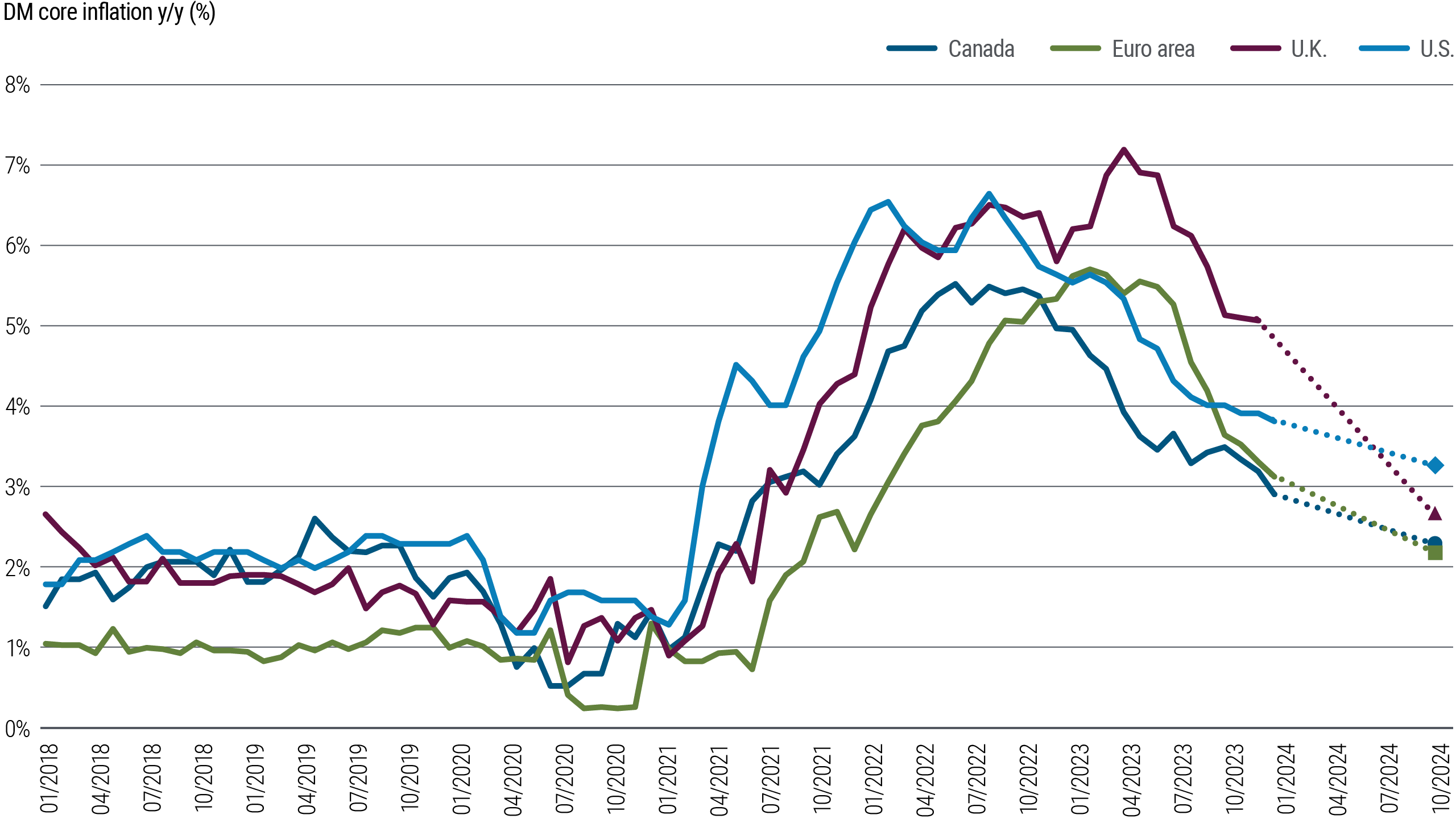

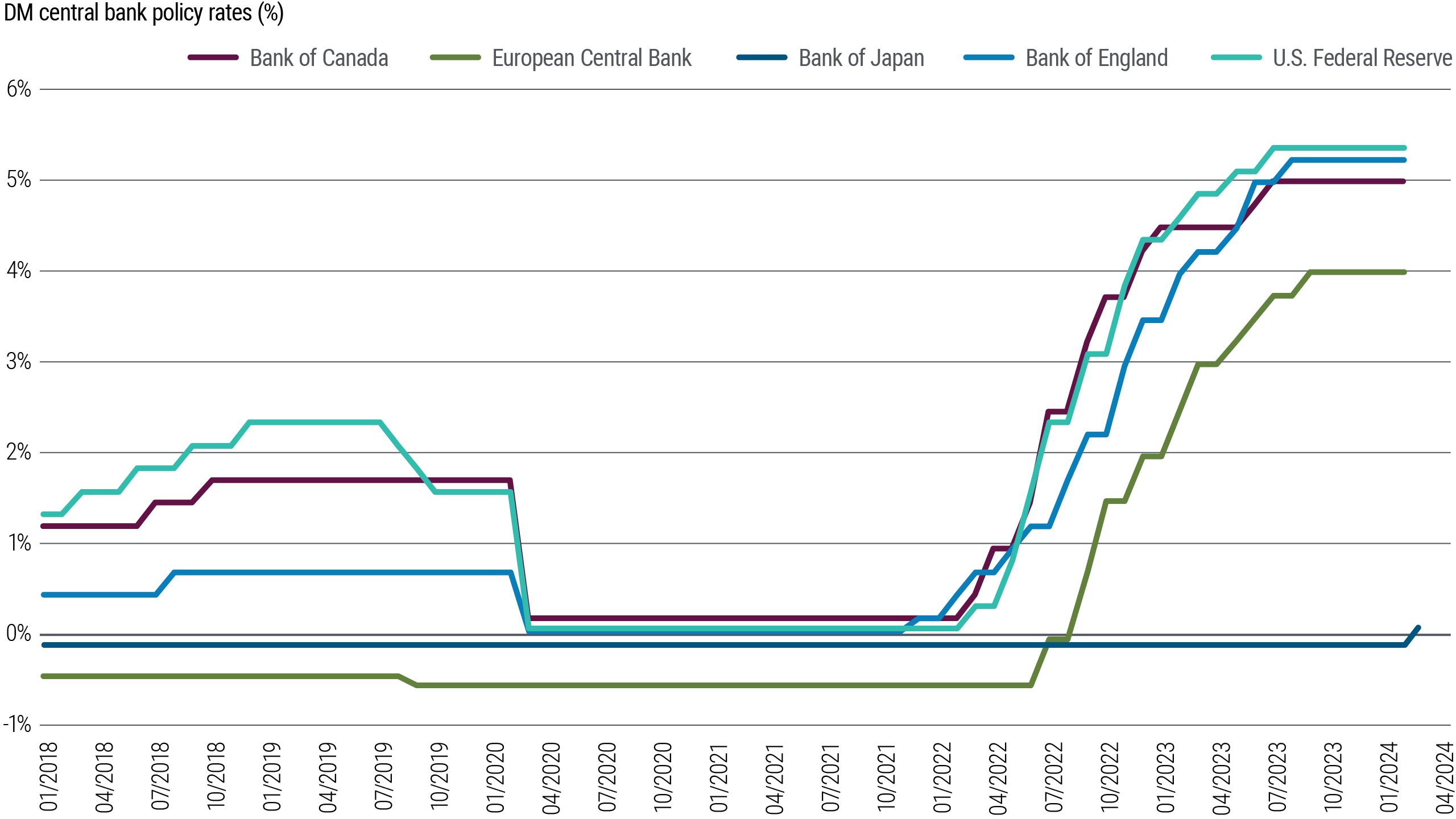

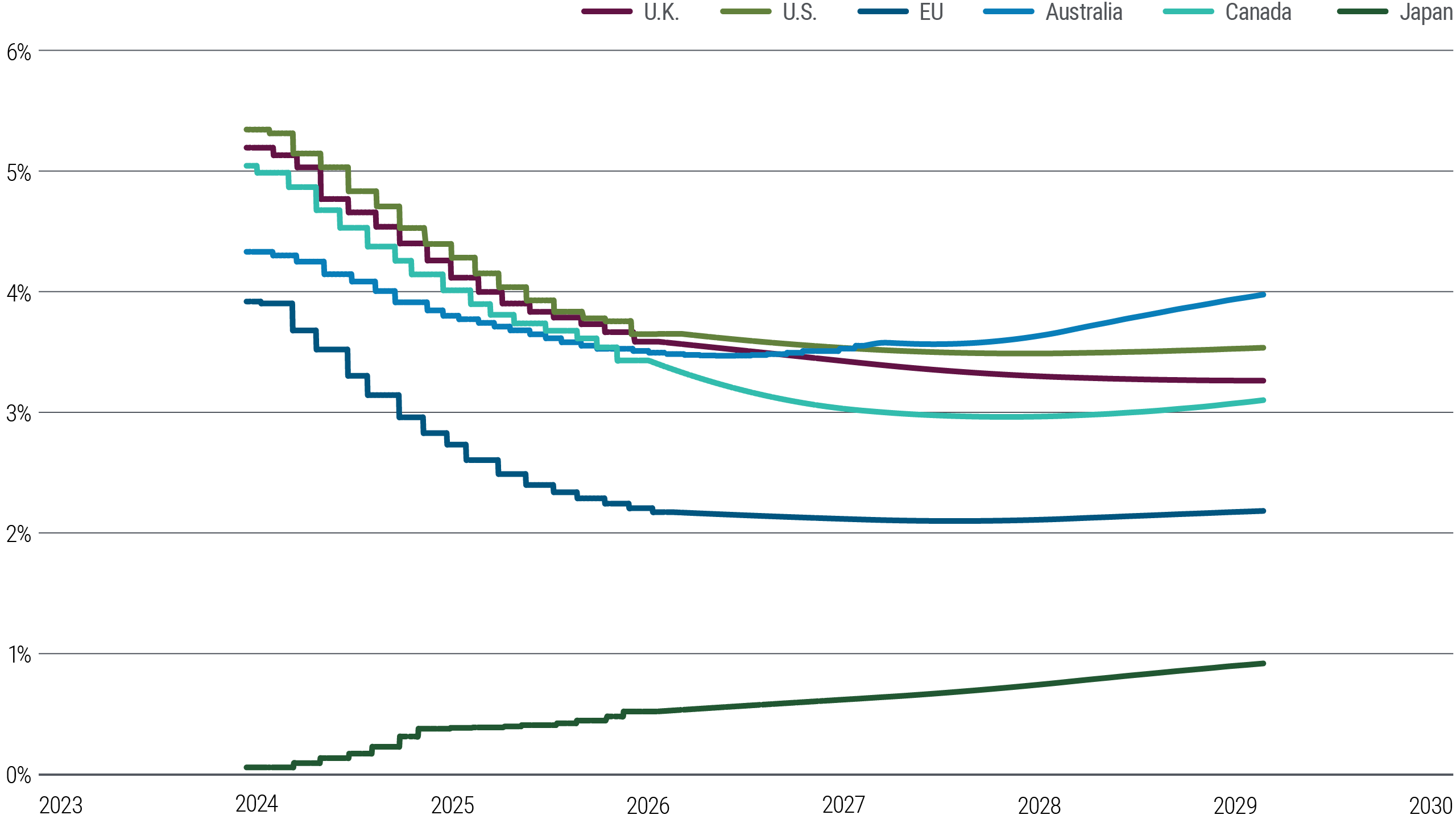

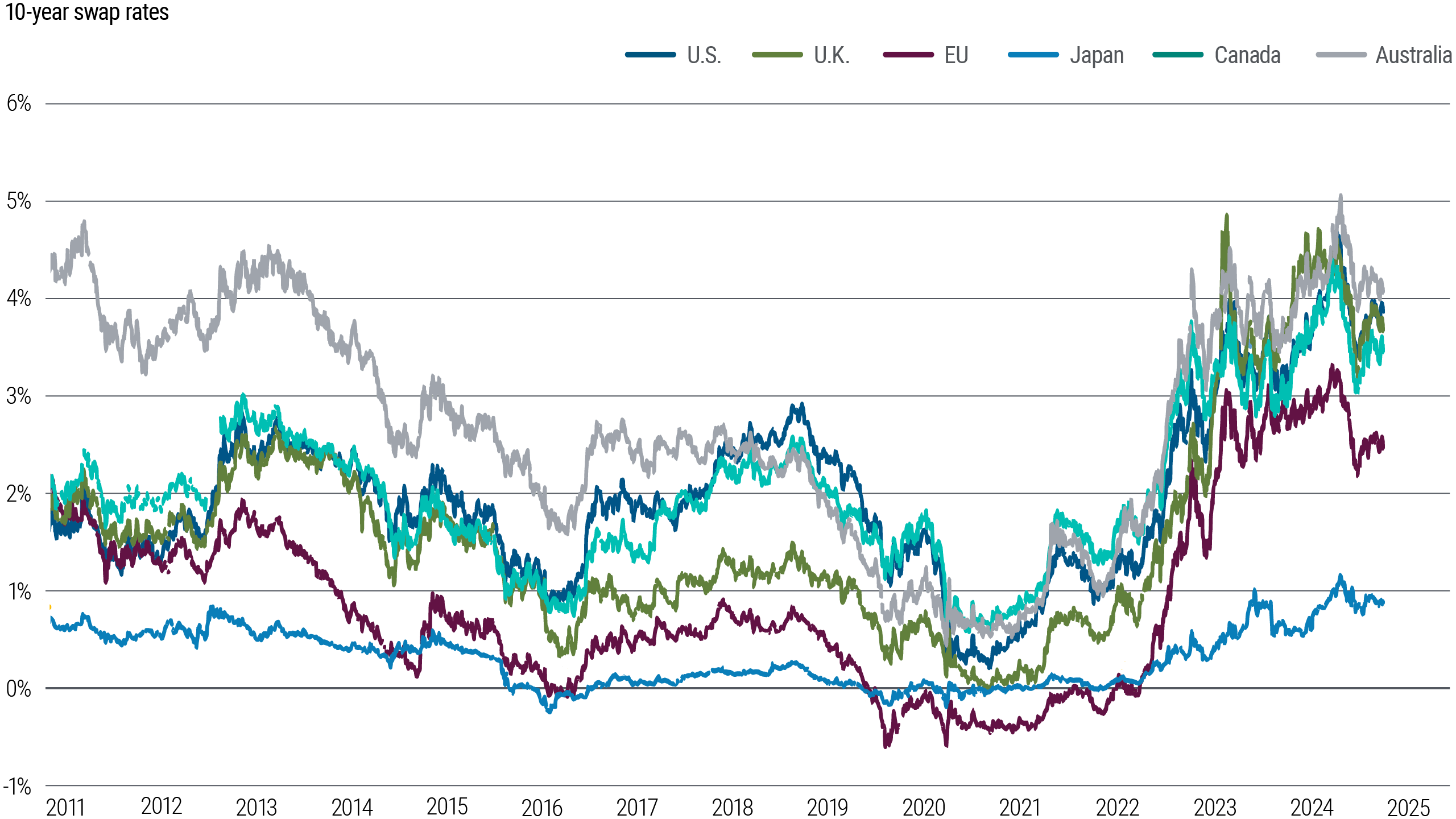

Diverging Markets, Diversified PortfoliosThe global investment landscape is set to be transformed in the months ahead as the trajectories of major economies diverge more noticeably. Central banks, which tightened policy in unison to curb the pandemic inflationary spike, will likely follow varied paths when cutting interest rates. While many large, developed market (DM) economies are slowing, the U.S. has maintained its surprisingly strong momentum, with several supportive factors poised to persist. Those growth drivers could keep U.S. inflation lingering above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target over our six- to 12-month cyclical horizon. We still expect the Fed to start normalizing policy at midyear, similar to other DM central banks. However, the Fed’s subsequent rate-cutting path could be more gradual. An economic soft landing remains achievable in the U.S. Indeed, market pricing for both equities and the Fed’s terminal policy rate appears to largely rule out the possibility of a recession. Yet we believe risks in both directions – from recession to rekindled inflation – remain magnified in the aftermath of unprecedented global shocks to supply and demand. Amid this uncertainty, bonds offer attractive nominal and inflation-adjusted yields, plus the potential to weather a variety of economic conditions. Given today’s flat yield curves, we believe intermediate maturities can offer a sweet spot between cash, where yields are fleeting and will decline when central bank rate cuts begin, and long-duration bonds, which could face pressure from rising bond supply needed to finance growing sovereign debt. We see bond markets outside the U.S. as particularly attractive, based on our view that inflation risks are less pronounced in the rest of DM while recession risks loom larger. We particularly like the U.K., Australia, and Canada. Given U.S. resilience, we favor the U.S. dollar over the euro and other European currencies. We continue to favor U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities and other high quality assets for their attractive yield and return potential. With interest rates elevated, we see greater pressure on both corporate borrowers and traditional lenders such as banks. Within private markets, we see increasing opportunities in asset-based and specialty finance. Today’s environment underscores the importance of global diversification, prudent risk mitigation, and constructing resilient portfolios through active management. We expect the traditional inverse correlation between stocks and bonds to resume, with the potential for fixed income investments to appreciate if the pricing of recession risk rises again. Economic outlook: U.S. exceptionalism may persist amid global stagnationIn our January 2024 Cyclical Outlook, “Navigating the Descent,” we projected stagnant to modestly contractionary global economic conditions this year as the effects of tight monetary policy took hold. So far, that scenario has generally played out across all DM economies – except the U.S. Despite technical recessions in the U.K., Sweden, and Germany, and stagnant growth elsewhere, the U.S. economy has carried its surprising 2023 strength into early 2024 (see Figure 1). We believe that U.S. growth has likely peaked and will gradually decelerate toward the rest of DM this year. Yet the factors that have contributed to U.S. resilience could continue to support the (still-slowing) U.S. economy for a while longer. We would argue that there are five main factors at play: 1) Larger pandemic-related fiscal stimulus and still-elevated federal deficits have bolstered U.S. demand relative to other regions.To be sure, U.S. savings balances have dwindled materially, especially for households at middle or lower income levels, and will continue to be eroded by above-target inflation rates over our cyclical horizon – further reason to believe that U.S. growth will slow. However, estimated savings balances in other DM countries are more fully depleted. U.S. consumers have also been increasingly willing to take on more debt to smooth consumption. Therefore, some cyclical outperformance in the U.S. may continue. 2) Other economies are proving more sensitive than the U.S. to higher interest rates.In other DM economies, the pass-through of monetary policy happens rapidly via higher interest costs on consumer debt and shorter-term, floating-rate mortgages. By contrast, U.S. households with low fixed-rate mortgages have been more insulated from Fed hikes, while benefiting from higher yields on savings. Furthermore, tighter credit conditions and declining economy-wide credit flows haven’t had the usual effect of slowing growth, as still-elevated savings from government transfers have reduced dependence on credit. Despite weakness in U.S. regional banks, most holders of high quality, low-rate bonds – including the Fed, large banks, foreign reserve managers, and households (to name a few) – have weathered well the mark-to-market losses of higher rates without triggering a systemic event. Other areas of the economy that are more rate-sensitive, including the commercial real estate (CRE) and bank loan markets, remain a source of potential fragility. Overall, we believe these risks to the broader U.S. economy are manageable. 3) Europe and Southeast Asia appear less insulated than the U.S. from Chinese import competition.Recent U.S. legislation, such as the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), has promoted U.S.-based industries, notably through tax credits contingent upon domestic production. The U.S. also relies less on exports for economic growth than many countries, while it benefits from access to affordable domestic energy sources. Additionally, the U.S. continues to impose tariffs on Chinese exports. To sustain its growth objectives amid a deep property sector downturn, China has capitalized on its ability to subsidize its manufacturers. That has allowed producers to export inexpensive goods, especially in renewable energy investment categories such as electric vehicles and solar infrastructure. This will likely contribute to global deflationary forces, with varying regional impacts (see Figure 2). China is also seeking to broadly increase its production efficiency in lower-quality goods. Southeast Asian countries that have benefited from Western supply chain diversification could face pressure. At the same time, China has made high-end manufacturing a policy priority. The euro area, and Germany in particular, appear to be at a relative disadvantage. 4) U.S. companies are at the forefront of AI technologies, creating significant wealth effects even before productivity gains are realized.The U.S.’s leading position in the global AI innovation race is supported by a vibrant startup ecosystem, substantial private equity funding, and advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology. U.S. export controls, though imperfect, will likely continue to restrict China’s progress. The AI boom could be somewhat inflationary in the near term – based on the demand-boosting wealth effect of strong equity performance and deep pools of available capital – before the deflationary impact from higher productivity sets in. We are optimistic that AI can generate productivity gains over our longer-term secular horizon, even as questions about implementation lags and magnitude remain. 5) The balance of risks for the outcome of the U.S. presidential election leans toward policies that would be marginally supportive of U.S. growth and potentially detrimental elsewhere.The U.S. election in November looms as an inflection point for global geopolitics and trade, with shifting risks to the investment landscape that we will continue to monitor. Another Donald Trump presidency would likely put pressure on NATO and focus on more aggressive protectionist trade policies. This, coupled with domestic deregulation and an extension in certain tax cuts, could support U.S. growth and inflation cyclically, despite potential longer-term costs to domestic productivity and economic dynamism. If President Joe Biden were to win another term, he would likely extend many of the 2017 Trump tax cuts, expand the Child Tax Credit, and keep, if not grow, the U.S.-oriented industrial policies put into place in his first administration. Implications for inflation and global divergenceThose factors supporting relative U.S. growth are also likely to contribute to stickier inflation in the U.S. in 2024. As inflation cools globally (see Figure 3), we believe core consumer price index (CPI) inflation in the U.S may end the year in the area of 3% to 3.5%. Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation, the Fed’s preferred gauge, could be in the 2.5% to 3% area at year-end, in our view, while inflation in the euro area could average 2% to 2.5%. With policy rates at cyclical peaks (see Figure 4), DM central banks are broadly signaling a midyear start to their easing cycles. (For details, see our March blog post, “One Hike, Three Hints, and a Surprise Rate Cut.”) We believe the pace of subsequent cuts could be faster, and the year-end 2025 destination rate could be lower, outside the U.S. Although a soft landing that avoids recession appears within reach across regions, significant uncertainties remain. A positive shift in economic supply, decelerating inflation, and falling rates have been key characteristics of past soft landings, according to our analysis of central bank rate-hiking cycles from the 1960s to today. All of these elements gained traction in 2023. Nevertheless, when examining the distribution of risks, we expect both inflation and recession risks to remain higher than usual in the wake of the unique disruptions caused by the pandemic. In the U.S., persistent inflationary risks look most elevated. Elsewhere, recession risks are still a chief concern. A critical factor will be the degree of leeway central banks have in tolerating inflation levels that exceed their stated targets. The Fed, unlike other central banks focused solely on price stability, has a broader dual mandate that includes managing the trade-off between inflation and employment. As a result, it would likely take a notable reacceleration in U.S. inflation across a broad range of components for the Fed to consider hiking rates again, which officials have indicated they would prefer not to do. That suggests the balance of risks related to Fed policy may tilt toward more rate cuts, despite remarkably resilient labor markets, which in turn may support somewhat above-target inflation for a while longer. The extent to which the Fed is willing to accept somewhat above-target inflation for any extended period remains a key question for the outlook. Investment implications: seeking global opportunitiesThe outlook for fixed income investing remains appealing, given elevated nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) yield levels and bonds’ potential to withstand many economic scenarios. Our view that economic risks are more skewed to the upside in the U.S., and to the downside in the rest of DM, leads us to a greater-than-usual focus on bond markets outside the U.S. There is little difference today between yields on short- and long-dated bonds. That uncommonly flat yield curve means investors can find value without significantly extending duration, a gauge of sensitivity to changes in interest rates that generally coincides with extending maturity. Short maturities – in the U.S. and elsewhere – price in comparatively low recession risk over the next few years, when comparing expected terminal policy rates with standard estimates for neutral rates (see Figure 5). We expect a more normal pattern of negative correlation between bonds and equities to reassert itself, with the potential for fixed income to outperform in the event that the pricing of recession risk rises again. For example, Chair Jerome Powell in March said the Fed is poised to cut rates if unemployment rises, even if inflation remains above the Fed’s target, potentially supporting bonds in a downside economic scenario that could challenge riskier assets. Intermediate maturities offer attractive yields along with potential price appreciation if bonds rally. They also appear compelling at a time when cash yields are poised to fall if central banks cut rates from current elevated levels. Duration and yield curveTo illustrate our views on duration and the yield curve, it helps to review how our stance has evolved. Last October, when the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield rose toward 5%, we said duration looked attractive while yields appeared high relative to our expectations. Then in December, a shift in Fed communication temporarily caused front-end rate markets to price in greater central bank easing than we anticipated. Today, with the U.S. 10-year yield around 4.25%, we remain broadly neutral on duration. We also see the pricing of short-dated yields as broadly fair and in line with our expectations for the baseline over our cyclical horizon. We maintain a slight duration underweight in U.S and global core bond portfolios, reflecting a recent market rally, but our focus remains on strategies related to global relative value and yield curve positioning. We have an underweight view toward the long end of the U.S. curve due to concerns about fiscal policy and Treasury supply (for more, see our February PIMCO Perspectives, “Back to the Future: Term Premium Poised to Rise Again, With Widespread Asset Price Implications”). Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) offer reasonably priced protection against upside U.S. inflation scenarios. Regional diversificationWhile we still find many areas of U.S. bond markets attractive, we currently favor DM outside the U.S., including countries such as Australia, the U.K., and Canada (see Figure 6), which we see as valuable global diversifiers. In Australia, the central bank has removed its policy-tightening bias. Yet the path of rate cuts priced into the forward curve looks relatively shallow versus other markets, especially given Australia’s elevated household leverage and floating mortgage rates that foster more direct transmission of monetary policy changes into the economy. We see U.K. duration as attractive given current valuation, an improving inflation picture, and the potential for the Bank of England to deliver more cuts than are currently priced into markets. Similarly, in Canada, we see the balance of risks skewed toward greater central bank easing compared with current market pricing given an improved inflation outlook. European markets look somewhat less attractive but offer important benefits such as liquidity (market depth and the ease of buying and selling assets) and diversification. They could also perform well if upside U.S. economic risks or downside European risks are realized. In the eurozone, we see expectations for the European Central Bank (ECB) and the level of 10-year yields as broadly fair versus the U.S. in our baseline economic scenario. Yet we see the balance of risks as leaning toward weaker economic performance and more easing from the ECB. We also prefer the U.S. dollar over the euro and other European currencies such as the Swiss franc and the Swedish krona, anticipating further U.S. economic exceptionalism. In keeping with the theme of global divergence, the Bank of Japan’s policy tightening leads us to a modestly underweight view on Japan duration (for more, see our March blog post, “Bank of Japan’s Policy Shift Ushers in a New Era for Investors”). Emerging market (EM) debt offers an attractive source of carry and diversification amid supportive global economic and monetary policy conditions. That said, we find relatively less value in local and external EM debt today when compared with DM. We believe currency exposure is currently the best way to express our EM outlook. Emphasis on credit qualityLooking at other areas, we continue to view U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) as very attractive. More broadly, we continue to favor high quality non-agency MBS, commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), and asset-backed securities (ABS). We expect to be overweight in credit derivative indices, high quality financial and industrial debt, and select high yield bonds. Active investment management and independent credit analysis can help identify winners and losers among companies and sectors in today’s economic landscape (for more, see our February video, “High Quality Credit Opportunities”). Given the yields available on high quality credit, we continue to urge caution on lower-quality and less liquid corporate positions that are more economically sensitive and would be vulnerable if downside risks materialize. In private credit markets, we continue to favor high quality, asset-based lending, as the theme of bank retrenchment continues to play out amid elevated interest rates and a complex regulatory backdrop. We favor various forms of residential mortgage and consumer lending, aviation finance, and broader opportunities to partner with banks as they seek to dispose of diversified portfolios of performing asset-based credit. Challenges in the existing stock of private credit will also create opportunities for flexible capital. This is especially true in floating-rate real estate and corporate credit markets, as elevated interest rates pose challenges for certain highly levered borrowers. We expect an attractive environment to deploy capital opportunistically, focusing on hybrid investments that have a combination of debt-like characteristics, with potential for equity-like upside. In summary, our strategy reflects a cautious yet opportunistic approach to navigating a divergent economic landscape, emphasizing global diversification with a focus on quality and value. |